Individuality contra society

There are times when we feel disposed to defend what's right and truth in spite of the majority. After all, what would become of the public welfare without any Socratic gadflies? Nevertheless, home truths may push whole societies beyond their "comfort zone" and compromise their—sometimes blameworthy—prosperity.

Then again, what good can truth or new ideas bring? Perhaps the public benefits most from the old, established ideas it already has. Rousseau[1] and Hegel[2] have claimed that the people do not always understand what's in their own best interest. And what if the prevailing conception of common good clashes with right and truth..?

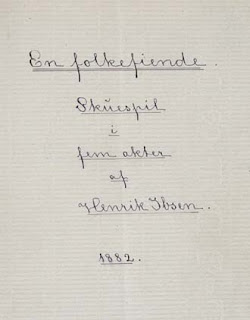

For example, in Henrik Ibsen's 1882 theatrical play "An enemy of the people" (original title: En folkefiende) the main protagonist, Dr. Thomas Stockmann, strives for right and truth, while firmly opposing widespread beliefs regarding the place of individuals in society and the value of "majority truths".

Stockmann—a man of science—discovers that the water of the municipal baths, which are the only source of economic growth for the local community, is contaminated and thus dangerous to use. He feels committed to informing his fellow-citizens in order to protect his town and any potential visitors to the baths from harm. Conversely, Stockmann's older brother, who serves as the town's mayor and the chairman of the baths' committee, vehemently disagrees with this idea: such a revelation would be economically and socially devastating.

The relationship between science, society, politics and power is truly a knotty one. Who's the real friend of the people and who's his enemy? Is it the one who wants to warn his fellow citizens by exposing the truth, or the one who prefers a cautious approach intending to safeguard the community from economic collapse?

We should ponder on this contrast, because societies are largely characterized by such conflicting perspectives. The fiery and misarchist Stockmann wants to fight

the lies that pervade society—the poisoned waters of the baths symbolize

the falsities on which the town's flourishing depends—and scorns the mayor for wanting to

cover up the truth. On the other hand, the mayor wants to minimize the

likely enormous financial, social and, in the end, political costs of

anyone involved—his own reputation is deeply intertwined with the common good.

Whereas practical politics are usually devoid of moral considerations and may involve hypocrisy and deception, individual conscience can be rebellious and uncompromising. Hegel remarks that the tendency to look inwards and decide from within oneself

what is right and good "appears in epochs when what is recognized as

right and good in actuality and custom is unable to satisfy the better

will"[3]. That is, Stockmann revolts against the status quo, because his sense of judgement denounces what is recognized by the authorities as right and good—i.e., the interest of the public based on fraud and trickery—as null and void.

|

| Cover page of the original manuscript, 1882. |

[1] J-J. Rousseau, Du Contrat Social (1762), Flammarion, Paris, 2001, II, VI, p. 74.

[2] G.W.F. Hegel, Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts (1821), Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1970, § 301, p. 469.

[3] G.W.F. Hegel, Ibid., § 138, p. 259; Elements of the Philosophy of Right, trans. H. B. Nisbet, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 167